The great city of Constantinople, known to the Vikings as Miklagard (The Great City), was a focal point for Viking activity in the medieval period.

Spanning over 300 years, the Vikings’ relationship with Constantinople was complex – ranging from hostile attacks to mutually beneficial trade and mercenary service. This article explores the fascinating interactions between these two civilizations.

Key Takeaways

- Miklagard (Constantinople) fascinated Viking traders and raiders, becoming a key focal point for maritime expeditions over centuries. Its immense wealth and strategic location drove this interest.

- After initial raids, Miklagard’s rulers opted to pay tributes to limit violence and also tapped into Vikings’ skills as mercenaries – most famously in the elite Varangian Guard.

- Many Vikings ultimately assimilated into Byzantine society after generations of service and settlement in Constantinople, while still retaining awareness of their northern heritage.

- Runic carvings and burial sites across eastern trade routes offer archaeological proof that Vikings traveled extensively between Scandinavia and Miklagard for trade and in military campaigns.

The Vikings: Not Just Raiders But Also Traders

The Vikings were often stereotyped as bloodthirsty raiders, but they were also prolific traders seeking valuable goods to bring back north. They established trade routes and outposts spanning from their Scandinavian homeland across Europe and even as far as the Middle East and Asia. Key goods brought back included:

- Jewellery

- Silver

- Silk

- Wine

- Spices

In exchange, the Vikings provided furs, honey, iron tools and weapons, and slaves captured on their voyages. This desire for far-off riches motivated their journeys south to regions like Spain and Constantinople.

Easy Access Via Rivers

Using a network of rivers and strategic portaging (carrying boats between waterways), the Vikings were able to reach Constantinople relatively easily from their northern bases. Archaeological evidence shows Viking presence along these river routes in places like Latvia, Russia and Poland.

Huge troves of dirham silver coins from the Middle East and Asia have also been discovered in Swedish archaeological sites – clear evidence of trade with Constantinople.

The founding of Viking trade outposts like Novgorod in Russia gave the Vikings critical access to river networks leading southwards to the Black Sea and Constantinople.

Some scholars credit the early Viking rulers of Novgorod, like legendary leader Rurik, with establishing the first foundations of what would eventually become the Russian state.

Miklagard: A Place of Awe and Wonder

To Viking eyes, Constantinople would have been an awe-inspiring sight – a bustling metropolitan capital at the center of the civilized world. Its magnificent architecture, wealth, and strategic trading position on the Silk Road captivated Viking travelers.

Some historians believe the Vikings’ positive impressions of the city even shaped its name in Old Norse – Miklagard (The Great City). This name persists in some Nordic languages today, such as Icelandic (Mikligarður) and Faroese (Miklagarður).

The Vikings clearly respected and admired the might and sophistication of the Byzantine capital. However, its riches also made tempting target for periodic plunder.

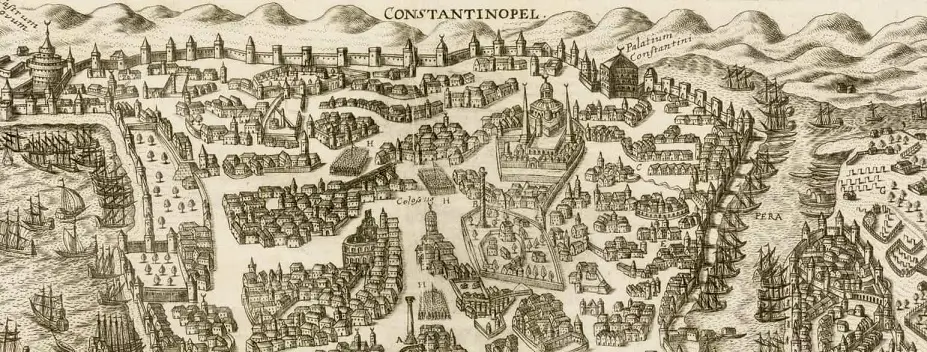

Miklagard – Credit Image

Attacks and Tributes

The Vikings first attacked Constantinople in 860 AD, accessing the heart of the city by sailing directly into the Golden Horn harbor. With its formidable defenses breached, the Vikings pillaged widely, burning buildings and churches, robbing treasuries, and killing inhabitants.

Facing repeated attacks, Emperor Michael III eventually opted to pay the Vikings tribute to spare his city from further assaults.

The Byzantine rulers also restricted Viking traders to specific docks in the harbor, with limited numbers (no more than 50 men) allowed within the city walls at any time. They were forced to surrender their weapons during the visit.

So the early Viking relationship with Constantinople was punctuated by both violence and trade. However, in time the Byzantine leadership decided these fierce northern warriors could better serve the empire as allies.

The Varangian Guard

In 980 AD Prince Vladimir of Kiev gifted Byzantine Emperor Basil II 6,000 Rus (early Russian and Scandinavian warriors) to serve as the new Varangian Guard. This elite unit became renowned as the most prized mercenaries of the medieval era.

They were the highest paid imperial soldiers, earning such riches that bribes were required for entry into the guard. Membership was highly desirable because the Varangians received shares of plunder from successful battles and special rights to pillage the imperial palaces when an emperor died.

Clad in their signature battle axes and chainmail armor, the loyal Varangians saw combat across the Byzantine domains for over 300 years until the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453.

They played a pivotal role in many campaigns in Italy, North Africa, the Middle East, and eastern Europe over the centuries – earning a legendary reputation as the empire’s most fearsome shock troops.

The best-known Viking commander of the Varangian Guard was Norway’s future king, Harald Hardrada. Before claiming his country’s crown, Hardrada spent many years serving as a Varangian officer, leading the elite guard on campaigns across the Mediterranean world.

Harald Hardrada

During his time in Constantinople, Harald amassed tremendous wealth from plunder seized in the army’s battles and raids. He strategically sent most of these treasures back to Russia for safekeeping by his family connections there. One historical account noted:

“There was an accumulation of wealth such that no man of the north had seen in the possession of a single man.” This fortune later helped Harald finance his bid for the crown upon finally returning to Norway.

While a prominent Varangian commander, Harald’s service in Constantinople ended under scandalous circumstances. Accounts suggest Hardrada unsuccessfully schemed to force marriage upon a Byzantine princess named Maria.

For this unauthorized romantic pursuit, Hardrada was imprisoned by the emperor – only escaping captivity after bribing his guards. Before fleeing Constantinople by ship, Harald brazenly kidnapped Princess Maria and absconded into the Black Sea.

However, he later opted to release the hostage bride before returning home in 1045. Despite this drama staining his departure, Harald Hardrada’s earlier military feats and cunning earned him ongoing renown back in Scandinavia – setting the stage for his eventual rise to become Norwegian king in 1047.

Integration of Varangians into Byzantine Culture

The loyal Varangians not only defended the Byzantine throne over centuries but gradually assimilated into local culture themselves.

They initially maintained awareness of their distinct Scandinavian roots while adopting Orthodox Christianity and Byzantine customs. Intermarriage became common over generations.

One small but symbolic example of Byzantine-Viking intermixing is seen in the town seals of certain Swedish communities like Täby.

Imprinted there alongside standard Nordic iconography is the classic Byzantine cross – suggesting hometown pride in a special eastern connection through their resident imperial guardsmen.

Other cultural artifacts similarly fused aspects of both worlds as the Varangian presence persisted through the 12th century.

Byzantine scholars’ records also noted the distinct Scandinavian lineage and tongues persisting amongst descendants of the Viking imperial guard even as they became more culturally “Byzantine” overall.

So in many ways, the Vikings sent to Constantinople as gifts from foreign rulers initially served as outsider mercenaries but gradually became ingrained fixtures within the highest ranks of the Byzantine military for centuries.

Their cultural identity transformed substantially over this long period while still retaining some awareness of distant Viking roots for generations.

Decline of the Varangian Presence

By the early 13th century, recurrent conquests of Constantinople by both Western European and Persian invaders had significantly eroded Byzantine power and autonomy.

The once-mighty empire struggled militarily and financially. As a result, records suggest the formal Imperial Varangian Guard phased out under weak or absent leadership. Veteran members dispersed elsewhere while influxes of replacements from the north slowed to a trickle.

However, the descendants of earlier waves of transplanted Scandinavian mercenaries remained woven into the urban population during this period of instability.

Some evidence indicates informal contingents of former guardsmen still organized to independently defend select locations like Constantinople from Latin crusaders during the 1204 siege.

These enduring vestiges of the Varangian community lacked their once-elevated status but temporarily assumed ad hoc defensive roles given deep roots within the capital.

But by the mid 13th century, the Crusader sack of Constantinople coupled with the parellel Mongol invasion of Rus territories choked off any lingering military or cultural ties back to Scandinavia.

Isolated outposts clung to awareness of shared Viking ancestry in Constantinople but the special conduits of communication no longer channeled fresh migrants or troops from the north.

The sustained existence of “Varangians” in Constantinople entered its fading, final era… only to vanish upon Turkish conquest in 1453.

This concludes an expansive overview documenting the nearly 600-year Viking imprint upon Constantinople (Miklagard) – the dynamic eastern crossroads between Scandinavia, Russia and the Byzantine realms.

Evidence of Vikings in Constantinople

Various forms of archaeological and literary evidence attest to the long-running Viking presence in Constantinople:

Archaeological

- Viking artifacts (weapons, jewelry, pottery) across the river trade route to Constantinople.

- Viking burial sites in places like Estonia and southern Russia along these eastern trade routes.

- A excavated Viking neighborhood inside Constantinople itself (in the suburb of Bathonea).

Runic Script

- Runic graffiti carved into marble arches inside the original Hagia Sophia church.

- Runic inscriptions on many runestones in Sweden commemorating warriors who served in the Varangian Guard. These stones include motifs like the Byzantine cross – proof of their link to Constantinople.

Eyewitness Accounts

- Numerous chronicles by Byzantine historians remarking on the presence of “barbarians from the North” in Constantinople – both as hostile raiders and imperial guards.

- References to Miklagard in many medieval Norse sagas, detailing voyages taken there by adventurers and royal figures like Norwegian King Harald Hardrada during his service in the Varangian Guard.

Miklagard FAQs

Why was Constantinople called Miklagard?

The Vikings referred to Constantinople as Miklagard (The Great City) in awe of its incredible size and splendor compared to northern European cities of their era. Even today “Mikligarður” endures in certain Nordic languages like Icelandic.

What does Miklagard mean in English?

Did the Varangian Guard defend Miklagard successfully?

The loyal Varangian Guard were the elite mercenary force of the Byzantine emperor for over 300 years. Clad in mail armor and armed with heavy battle-axes, they saw combat across the empire. However, the Varangians could not stop the eventual conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks in 1453, heralding the final collapse of the Byzantine Empire.

Where is Miklagard now?

Miklagard later became known as Constantinople after Emperor Constantine’s establishment of this Eastern capital. Today this legendary city is known as Istanbul, a sprawling Turkish metropolis situated on the Bosporus straits dividing Europe and Asia.

Conclusion

Over nearly 300 years, Miklagard (Constantinople) played an integral role in Vikings’ expansive trade networks and military exploits spanning eastern Europe and the Middle East. The city’s immense wealth and prestige fueled a complex dynamic between the Byzantine Empire and Norse raiders and merchants.

This relationship fluctuated dramatically over time – ranging from violent pillaging to lucrative trade partnerships to the revered service of Viking warriors protecting the emperor in the legendary Varangian Guard. Archaeological evidence and colorful historical accounts attest to the enduring Viking presence interwoven into the fabric of Miklagard’s cosmopolitan streets.

The Vikings’ legacy in Miklagard finally faded in the 15th century after the Turks seized the city. But this eastern crossroads indelibly shaped Scandinavia’s outlook and connections to the broader medieval world during the apex of Viking exploration and conquest.

Shop Viking Jewelry

Are passionate about Vikings or Norse Mythology?

Finding the ideal piece of Viking Jewelry can be challenging and time-consuming, especially if you lack inspiration or don’t know where to look.

Surflegacy, has you covered. We have a wide range of Handmade Jewelry in various styles, shapes, colors, and materials, to accentuate your Viking spirit and look. Do not hesitate to visit our selection HERE