The Ulfberht sword has come to light in numerous Viking tombs. It is nearly indestructible and perpetually sharp, so much so that it rivals the famous Japanese katana. It dates from between the 9th and 11th centuries AD. On the blade of the 167 specimens found, the same name always appears: +VLFBERH+T.

A name of Germanic origin accompanied by crosses. Who was the mysterious Ulfberht? The ingenious smith who discovered the recipe for making the sword of swords?

Ulfberht swords exhibition in Berlin 2014

What is the Ulfberht sword made of?

The common characteristic of these swords, besides the signature we will discuss later, is the incredible steel from which the blade is made, called crucible steel a very pure steel that has posed experts and scholars with the difficult challenge of understanding the forging processes of the time.

It is indeed a steel worthy of that obtained by modern industrial processes, which, with the technology of the time, seems impossible.

Ulfberht has about three times the carbon content of other swords of the time, which determines its main characteristics: flexibility, strength and lightness. Its steel is much more compact and has fewer discontinuities due to slag.

The Ulfberht swords were forged from crucible steel, which was uncommon in the Middle Ages. Because it was cast in a crucible, this steel burned much hotter than modern steels, removing most, if not all, of the slag that was common in steels at the time.

It is necessary to reach 1,538 degrees Celsius to liquefy the metal and allow the removal of impurities. Prior to Ulfberht’s discovery, it was thought that removal of impurities at these temperatures was only possible during the Industrial Revolution, but Ulfberht’s smithies achieved the same results, apparently 800 years earlier.

Medieval and later blacksmiths removed impurities from iron by heating it to about 300 degrees and then mechanically beating it, without ever achieving the levels of Ulfberht’s steel.

Aside from the difference in smelting, swords made of this type of steel contained far more carbon – while most steels contained as much as 0.520 percent carbon, the steel of an Ulfberht sword contained as much as 1.2 percent to 1.6 percent. Steel with this carbon content is classified as spring steel in modern classifications.

What is so special about Ulfberht sword?

As a result, the Ulfberht sword was far stronger and more flexible than standard medieval steel. It could bend when thrust at a hard object, such as a shield, whereas other swords would crack, break, or shatter under such duress. They were a secret weapon that was originally not to be sold outside the German territory of Franconia

What was originally meant to be the name of the blacksmith and inventor became a kind of trademark. It indicated the workshop-and thus a particular technique by which the swords were made.

But where did these weapons come from? What was their secret? Why were the blades different from those of all other medieval swords?

Origins of the Ulfberht Sword

That’s right, the origins of Ulfberht swords lie in Germany. And not in Scandinavia, as was mistakenly written recently after the release of a BBC documentary whose authors wanted at all costs to attribute this product of military technology to the Vikings.

Nothing could be more wrong. The Vikings probably came into possession of the swords during their raids from one territory to another, as several Ulfberht specimens have been found in the graves of northern warriors. But they did not possess the technology to produce such blades.

Vikings, however, are making a comeback in recent times, and those who devised the British documentary have cleverly exploited the current trend.

The German authorship of Ulfberht swords, on the other hand, has been definitively confirmed by the discovery of a specimen in Lower Saxony (Niedersachsen, Germany).

The weapon helped shed light on the mysterious genesis of these incredibly evolved weapons. By chance. An excavator fished out of the Weser River, near the town of Hessisch Oldendorf, an Ulfberht sword about a meter long.

The weapon has the typical inscription and dates back to the 10th century AD.

Subjected to an analysis by the Institute of Inorganic Chemistry at the Leibniz University of Hanover and in the opinion of chemist Robert Lehmann, the lead used to make the decorations on the sword’s hilt came from the mountains of the Schiefergebirge massif.

More precisely: from an area of Franconia located between the Rhine River, the Lahn and Wetterau. It is therefore likely that Ulfberht’s workshop was located in the renowned monastery in the city of Fulda.

In the vicinity of the monastery was the Schiefergebirge mountain range, from which the monks obtained the lead necessary to build the blade.

But even before these laboratory analyses were carried out, scholars had already assumed that the area of origin of the Ulfberht swords was Franconia.

Following philological research. Indeed, the letters of the Latin alphabet engraved on the blade in the Carolingian manner, as well as the accompanying crosses, had immediately suggested that it was the workshop of a convent. After all, Ulfberht is a Frankish name, not a Scandinavian one.

In the Sankt Gallen monastery cartolary it appears in several variants, such as Uolfberht, Wolfbert or Uolfbertus.

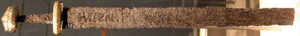

The sword found in Lower Saxony

The weapon found in Lower Saxony is the first Ulfberht sword specimen examined by means of computed tomography and is amazing the Ulfberht’s high technology: the quality of the blade made of sturdy tempered iron with a high percentage of carbon is equivalent to that of modern steel.

The blade always remained sharp. When the specimen was finished, the inscription +VLFBERH+T, an iron inlay, was applied to the blade.

The name Ulfberht

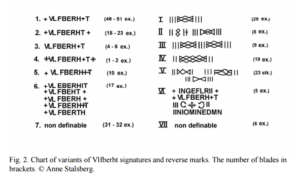

Let us begin with the name engraved on the blade. This name has many variants, as pointed out and classified by Anne Stalsberg in her essay The Vlfberht sword blades revalued.

Diagram of the different spellings of the Ulfberht signature and symbols engraved on the back,from Anne Stalsberg, The Vlfberht sword blades reevaluated

For a long time, it was thought that the variants indicated copies or fakes produced by different workshops that had added the name to increase the value of the sword, as is the case today for famous brands such as Gucci or Prada.

However, it has been shown that the only way to ascertain the originality and genuineness of an Ulfberht sword is to analyze the quality of the steel.

Rather, the different forms of the signature can be attributed to the fact that the smiths were essentially illiterate, almost certainly slaves, who could make mistakes in reproducing marks that were not meaningful to them.

It should also be considered that once the steel was engraved, it was not easy to correct the error without having to throw away all the work and reforge the sword.

In a case that, given the preciousness of the weapon, certainly did not occur, it is preferable to eventually adapt the name in a new spelling.

The idea that Ulfberht is the name of a single smith is obviously to be dismissed out of hand, given the time and geographical span of sword distribution. Rather, it must indicate a technique, a process of execution, and thus a quality guaranteed by the signature.

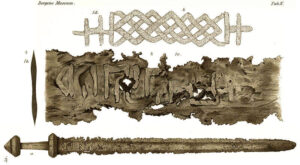

Sword of Ulfberht from 825, Nuremberg Museum.

Who was Ulfberht?

The presence of the cross clearly indicates a connection to ecclesiastical institutions. With the exception of no more than six signatures in variant 3, all signatures have an initial cross, in the shape of a Greek cross, in front of the V.

With the exception of very few signatures in variant 6, all signatures also have a second cross after or before the final T, perhaps two signatures even have three crosses, one initial, one before and one after the final T.

The crosses must mean something otherwise, they would not have been included in the signatures almost without exception.

There are three categories that have a cross in the signature: abbots, bishops, and monasteries of the Catholic Church.

In the records preserved in St. Gallen there are numerous documents of the time in which signatures are preceded by similar crosses.

It is therefore very likely that Ulfberht was an abbot or bishop, under whose leadership workshops dedicated to the production of weapons and the famous sword operated.

Obligations to supply predetermined quantities of weapons by church communities are often mentioned in the Capitularies, as in the case of the abbeys of Corbie, Fulda and St. Gallen.

Although the production of swords is not directly mentioned, it is at St. Gallen that the presence of “emundatores vel politores gladiorum” is mentioned.

The idea that a Carolingian monastery or abbey used illiterate slaves in its workshops is not surprising.

Alcuin, the adviser to Charlemagne and architect of the Carolingian revival, was the abbot of four abbeys that had about 20,000 slaves.

It also seems clear that literate slaves would have been employed in other roles rather than in the craft sector.

Drawing by Anders Lorange published in 1889 in a Norwegian archaeology journal; Lorange was the first to describe Ulfberht swords.

The Libri Confraternitatum Sancti Galli list many variants of this name between the 9th and 11th centuries: Uolfberht, Uolfbernt, Uolfbernus, Uolfberht/ Wolfbert, Uolfbertus/Wolfbertus.

These are always people closely associated with the Abbey of St. Gall: monks, abbots or benefactors. In a bequest from 802 a man donates his villa in the Lower Rhine area to an abbot in his and his father’s name.

In the manuscript, the father’s name, in the genitive, is spelled Wulfberti. Both the Abbey of St. Gall and the Lower Rhine area were within the borders of the Frankish kingdom.

Although no reference to the name Ulfberht or Vlfberht in this exact spelling has yet been found, it now seems established and recognized by all scholars that the name is Frankish.

The important evidence of lead

If the analysis of the name and symbol of the cross were not enough, an important piece of evidence for the Frankish origin of the extraordinary sword came recently, following the discovery of a specimen dating back to the 10th century, recovered in 2012 from the Weser River near the town of Hessisch Oldendorf in Lower Saxony (Niedersachsen, Germany).

Ulfberht Sword found in the river Weser

Subjected to an analysis by the Institute of Inorganic Chemistry at the Leibniz University of Hanover, it revealed, according to chemist Robert Lehmann, that the lead used to make the decorations on the sword’s hilt came from an area of Franconia located between the Rhine River, the Lahn and the Wetterau, exactly from the mountains of the Schiefergebirge massif located in the vicinity of the monasteries of Fulda and Lorsch.

It is therefore likely that Ulfberht’s sword workshop was located in one or both of these. Analysis has also established that the hilt and pommel were not made separately by different craftsmen, but in the same workshop.

The blade of this sword has a high manganese content, which led Lehmann to rule out the hypothesis that it could have come from the East. This suggests that the sword was forged near the source of the minerals used.

According to Alfred Geibig, curator of the Coburg Collection of Medieval Weapons and Armor, one of the largest in Europe, Western blacksmiths of the Middle Ages had a long and important tradition of making weapons, from the Celts to the Romans.

Unlike their Eastern counterparts who worked with Damascus steel, that is, a technique involving the casting of different types of iron of different temper, European smiths used mono steel for Ulfberht swords. Equally important to the material was the technique of processing and cooling the metal, which of course was subject to secrecy.

Distribution

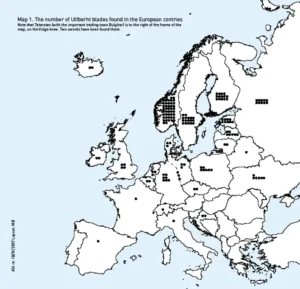

What has always suggested that the Ulfberht was the Viking sword par excellence is the huge number of such swords found in Scandinavia.

Distribution map of Ulfberht sword finds (from Anne Stalsberg)

It should not be forgotten, however, that the finding of most swords, both in Scandinavia and in the eastern territories, is due to the still pagan funerary ritual of laying down the weapons with the deceased.

This ritual was no longer permitted in the Christianized world of the Carolingians. It is no accident that the sporadic finds in Central Europe occurred at bogs or waterways rather than in necropolises.

This raises a further question. For we know from the Carolingian Capitularies that the foreign trade in “arma et bruniae (armor) atque caballi” underwent various restrictions over the years, ranging from an outright ban to authorized sales only for certain categories of merchants.

This is understandable, considering that the Carolingians certainly did not want a sword of the quality of the Ulfberht to come into the possession of even the fearsome Northerners who threatened Europe at that time.

In Charles the Bald’s Edictus Pistense of 864, the death penalty was proclaimed for those who traded weapons with the “Nortmanni” without royal authorization.

In light of this information, to give an explanation for the huge percentage of swords “passed on to the enemy,” it must be assumed that smuggling continued undaunted, which in fact corresponds to the need to reiterate the ban in numerous subsequent laws, and that the Vikings could come into possession of the deadliest weapon of the time in various other ways: depredation of the fallen in the field, looting and ransoms.

The strict and repeated control over the export of weapons is in itself also evidence of how much the general quality of the equipment produced by the workshops to arm the vassals was appreciated outside the Frankish borders.

In the Annales Bertiniani we read that the Saracens also particularly valued Ulfberht: in 869 they demanded one hundred and fifty such swords as part of a ransom for Archbishop Rotland of Arles.

Conclusion

Many points remain to be verified. It remains, for example, to find a clear reference linking Ulfberht’s name to blade production, just as all blades should be examined with reference to the manganese and lead contents that convince Lehmann of the European locality of origin. The symbols traced on the backs of the swords, so far set aside by scholars, should also be verified. However, the evidence known so far convinces us that the Viking sword queen is indeed Carolingian.

Where to find the ideal Viking Jewelry

Finding the ideal Viking Jewelry can be challenging and time-consuming, especially if you lack inspiration or don’t know where to look.

Surflegacy, on the other hand, has you covered. We have a wide range of Norse Jewelry in various styles, shapes, colors, and materials, to accentuate your Viking look.

Our pieces are crafted in Italy with care, style in mind, and reasonably priced, so you won’t have to break the bank to get one. Visit our store and let us assist you on your fashion journey.